By

Xavier Riaud

Oscar Amoëdo y Valdes was born in Mantazas, a village near Havana in Cuba, on November 10th 1863. Early in his teenage years, he started practising dentistry in Ricardo Gordon’s dental office, a local dental surgeon. The latter encouraged the young man to further his training at Dr Florencio Cancio Zamora’s Central Academy of dentists in Havana. He graduated with the highest honours. The student sollicited the dean of the university of the Cuban capital city in October 1884 in order to take the diploma of dental surgeon that he passed at the age of 21 years old. Inquisitive about all subjects, Oscar decided to enroll at the New York Dental College in the USA, where he graduated in 1888. Then, he returned to Cuba. There, he had an independent practice until 1889. He attended the first dental congress in Paris. Following this symposium where he was largely acclaimed, he settled in Paris and enrolled at the Faculty of Medicine. In 1897, he was asked to identify a body which was supposed to be that of Louis XVII from his teeth. After the examination of the teeth, he undoubtedly concluded that it was not the dead son of the beheaded king.

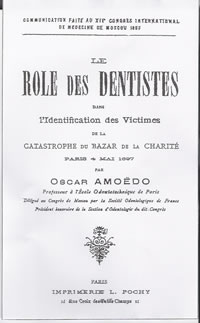

On May 4th 1897, 124 people died in the fire of the Bazar de la Charité because of a mishandling of the projectionist’s equipment (using a system of ether and oxygen rather than electricity) which caught fire. Many of the victims were aristocratic women, the most notable of whom was the Duchess of Alençon, Sophie Charlotte of Bavaria, sister of the famous Empress of Austria Sissi. Her body was the most charred. The next morning, around noon, about thirty bodies had not been identified. The consul of Paraguay had the idea of seeking the help of the victims’ dentists. Three dentists were then summoned to carry out the identifications: Dr Charles Godon, Dr Isaac Davenport and Pr Ducourneau, teacher at the Odontotechnical School of Paris. Dr Isaac Davenport, Sophie-Charlotte’s dentist, came with his client’s medical card: he had written 17 consultations which were completed over at least a two-year period, the last one dating back to December 15th, 1897. He identified her body and his statement was supported by the justice. It was a first for France. At the end, only five bodies were not identified. The practitioners’ work was reported by Oscar Amoëdo y Valdes during the 12th international congress of Moscow in a presentation entitled “The dentists’ task of identifying the bodies of the disaster of the Bazar de la Charité”.

On July 7th 1898, when he was 35 years old, Oscar defended his thesis in medicine The dental art in legal medicine and obtained the title of Doctor in medicine. Professor Brouardel, author of the famous legislation of 1892 which confered the dental surgeons an official status as we know it today, and president of the thesis jury, said of the candidate’s work: “This is not a thesis but a treaty of odontology. He filled in all the great gaps which remained in the field of forensic identification”. His colleagues’ experiences and fieldwork as well as his own knowledge allowed him to defend his thesis successfully. This work of 608 pages was published by Masson & Cie Editions. It was acknowledged as the authoritative source on this subject by the whole dental profession. This is when dental identification, which had been inexistent until then, was born. A great number of pages were devoted to the techniques of identification, bites, to the abrasion of teeth and to post mortem teeth. To complete it, he supervized the dental jurisprudence. He concluded his study with 52 observations devoted to dental identification. In addition, on August 4th, 1899, he presented with great conviction an essential communication entitled “The identification of corpses by a dental expert” to the American Dental Society of Europe. « The role of the dental expert in carrying out identifications cannot be called into question nowadays. The observations that we bring are sufficient converging arguments. Sometimes, the dentist uses special anomalies as the cornerstone of his conclusions; sometimes, he uses a restoring operation for the same goal. However, even though his observations often required the justice to call upon him, many times he was neglected. (…) His role could not be put into question and we think that in future, dentists will be called up in difficult situations and that it will be no accident; that was though about since the beginning and it will prevent painful surprises. »

Next to his study, he practised at the “Ecole odontotechnique” of Paris. He was successively appointed instructor, supply professor, and finally, full professor. There he taught on a voluntary basis for 15 years. To live, Amoëdo established his dental office. Even though, he started slowly, he eventually relocated to 15, avenue de l’Opéra and never left.

He wrote more than 120 various and differing articles about the technical aspects of dentistry. As a member of 14 learned medical societies, he attended 57 professional conferences.

On July 24th 1900, while he was facing scapegoating and jealousy, the Minister of Education signed an order upon the request of the Dental School of Paris, stipulating that Amoëdo was allowed to practise despite being a foreigner. On January 26th 1902, he was elected as an academician unanimously. From Paris, the Cuban dental surgeon contributed to the liberating revolution of his own country. His great pride was his nomination as president of the French odontological society.

His inaugural address showed his thrill for the dental profession.

During World War I, he was one of the first dentists to enlist in the Red Cross as dental practitioner. He also remained at the authorities’ disposal to treat those who needed him the most. On August 5th 1914, a relief committee was created. It aimed at treating the soldiers who had maxillofacial and facial injuries. It was made up of civilian dentists whose task was also to raise money to develop health care infrastructures for these injured soldiers. Oscar joined it immediately. As he was a recognized authority for the profession, he moved into the lead on that list. During the war, Amoëdo y Valdes was promoted to the rank of captain for his devotion. He was also made a knight of the Legion of Honor in France and was awarded a commemorative medal of the Great War. During World War II, the Germans imprisoned and transfered him in a camp. Oscar Amoëdo y Valdes died in Toulouse, on September 27th 1945. He was 82 years old.

Thanks to Amoëdo y Valdes’s work on forensic odontology, the status of dental experts was more recognised and noticeable throughout the 20th century notably in the context of judicial proceedings.

Dr Oscar Amoëdo y Valdes (1863-1945).

Dr Oscar Amoëdo y Valdes’ lecture at Moscou in 1897.

Duchess of Alençon’s dental file from Dr Isaac Davenport’s dental room.

|